Education is not the filling of a pail, but the lighting of a fire. - William Butler Yeats

Stuff I need for lessons

Monday, 26 January 2015

Hawthorne Public School's Community Cupboard

CBC Ottawa did a story about a project I am involved in at my placement school. You can view the t.v. news story here.

I will post a link to the radio story if and when it is up on the CBC

website. Big thanks to Julie Ireton at CBC for putting the story

together and getting needed exposure for the Hawthorne Community

Cupboard!

Narrative fiction in a content area

My “content

area” is history, specifically, Canadian History. And since I can

remember, I have always loved Canadian Historical fiction. One of my

favourite books of all time was (and is) Farley Mowat’s Lost in the Barrens, which I re-read this year and found to be as wonderful as I remembered it.

My “content

area” is history, specifically, Canadian History. And since I can

remember, I have always loved Canadian Historical fiction. One of my

favourite books of all time was (and is) Farley Mowat’s Lost in the Barrens, which I re-read this year and found to be as wonderful as I remembered it.This week in my writing class, I am to select an example of poetry or prose in my subject area. I immediately turned to Farley Mowat, this time The Curse of the Viking Grave, the equally enthralling sequel to Lost in the Barrens:

For me, this passage, succinctly and in the classic wordsmithing of Farley Mowat, paints the scene, develops the characters, and sets mood, and does so through the well-chosen adjectives of a gifted writer.(Chapter 1, page 2) Angus Macnair hardly looked the part of a school-teacher. He was a massive and craggy-faced trapper who had lived in the Canadian northlands since leaving Orkney Islands at the age of thirteen. The schoolroom was the Macnair cabin, a cluttered and low-ceilinged log structure redolent with the gamey smell from scores of pelts that hung drying from the rafters. Here Angus taught school for three days each week. During the remainder of the week teacher and students were absent from Macnair Lake, tending their traplines which ran for as much as fifty miles to the north, east, west and south.

The message that is conveyed to me in this paragraph is one that is more about the writer’s craft than the story, and I imagine that other readers, those not currently enrolled in a course about how to teach writing, might receive a different message from its reading. Perhaps they would understand more about the way children in the far north during this period were educated, perhaps they would focus on their understandings of survival and priorities in this community, or the diverse roles of community members or the contribution of children to their communities. How would they gather this meaning from the paragraph? Through the writer’s use of detail and descriptive adjectives, taking us back to the meaning I take from this paragraph: its function in writing to learn (using historical fiction) through learning to write.

In our textbook for this course (Writing Across the Curriculum, Peterson (2008)), Shelley Peterson suggests using a text such as this for a mini-lesson on The Challenge of Details. She suggests using a mentor paragraph but removing the details in the writing before sharing it with students. Students would then be challenged to form an image or picture of the scene or characters without the adjectives. After finishing that exercise in frustration, I would then share the original paragraph with the students and talk about the use of detail in good narrative writing and have the students form a picture of the scene or characters using the paragraph in its full form. To take the lesson further, I would challenge students to edit a paragraph from another historical narrative that has so much detail that it gets in the way of the narrative itself, having the students hopefully reach the analysis stage of their learning, and all through the use of narrative in a content area.

Thursday, 22 January 2015

A history mentor text: content and style all in one

Great mentor texts for Junior/Intermediate Social Studies and History students can be found in issues of Kayak Magazine: Canada’s History Magazine for Kids.

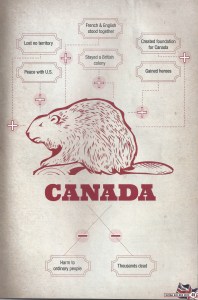

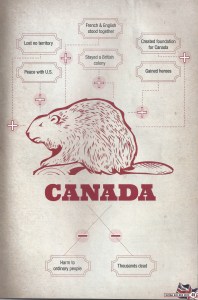

Below is a mentor text I chose. I like its presentation of the

Essential Question, evidence given for both sides of the debate, and

terrific use of visuals in the form of infographics:

Using the conventions of non-narrative writing styles described by Shelley Peterson in her book Writing Across the Curriculum (2008), I would identify this mentor text as an article, the intention of which is to inform or explain to the reader, the negative and positive effects of the War of 1812 on Canada and on the United States and present the reader with information to decide for themselves who came out of that war as the defeated and who came out as the defeater.

Kayak Magazine’s December 2012 issue is dedicated to the history of the War of 1812. This particular article summarizes the effects on both sides, after presenting a variety of other articles on particulars of the war. This article, and the issue in general, would be a valuable contribution to teaching Grade 7 History, Strand B: Canada, 1800-1850: Conflict and Challenges. The text gives valuable information on the topic that would spur debate and discussion on the question “Who won the war of 1812?” and it would also serve as a mentor text for how to present information on a topic through text and infographics in a way that allows a reader to learn and form an opinion.

The infographics for the Canadian and American experiences through plus and minuses is particularly effective. They summarize the information clearly, the images and colour make it easy to identify which side the infographic is referring to, and it provides an example of how to summarize complex information in a clear and concise manner.

I hope to be able to use this mentor text one day in a classroom setting.

Using the conventions of non-narrative writing styles described by Shelley Peterson in her book Writing Across the Curriculum (2008), I would identify this mentor text as an article, the intention of which is to inform or explain to the reader, the negative and positive effects of the War of 1812 on Canada and on the United States and present the reader with information to decide for themselves who came out of that war as the defeated and who came out as the defeater.

Kayak Magazine’s December 2012 issue is dedicated to the history of the War of 1812. This particular article summarizes the effects on both sides, after presenting a variety of other articles on particulars of the war. This article, and the issue in general, would be a valuable contribution to teaching Grade 7 History, Strand B: Canada, 1800-1850: Conflict and Challenges. The text gives valuable information on the topic that would spur debate and discussion on the question “Who won the war of 1812?” and it would also serve as a mentor text for how to present information on a topic through text and infographics in a way that allows a reader to learn and form an opinion.

The infographics for the Canadian and American experiences through plus and minuses is particularly effective. They summarize the information clearly, the images and colour make it easy to identify which side the infographic is referring to, and it provides an example of how to summarize complex information in a clear and concise manner.

I hope to be able to use this mentor text one day in a classroom setting.

Monday, 19 January 2015

One story of overcoming fear in writing

Last week, I read Nancy Atwell’s engaging introduction to her book In the Middle

(1998) that gave a glimpse into the in-the-trench action of writer’s

workshop with her students. Atwell takes readers on her evolutionary

journey from first-year-teacher, imposing fairly strict parameters on

her students’ writing, to a later version of herself as writing teacher,

giving her students free reign in regards to both the content of their

writing and the genre. It was refreshing to read about the success she

saw when she let her students have free reign to write. It was

interesting to contrast this to the approach of Shelley Peterson in her

book Writing Across the Curriculum,

who feels that teachers should set parameters for content and allow

creativity to exist within the parameters for form. Although I haven’t

yet had a chance to test either approach, I feel that I would subscribe

to Peterson’s approach over Atwell’s, as I have seen the befuddlement of

students when given complete carte blanche to pursue any avenue they choose in their writing.

Last week, I read Nancy Atwell’s engaging introduction to her book In the Middle

(1998) that gave a glimpse into the in-the-trench action of writer’s

workshop with her students. Atwell takes readers on her evolutionary

journey from first-year-teacher, imposing fairly strict parameters on

her students’ writing, to a later version of herself as writing teacher,

giving her students free reign in regards to both the content of their

writing and the genre. It was refreshing to read about the success she

saw when she let her students have free reign to write. It was

interesting to contrast this to the approach of Shelley Peterson in her

book Writing Across the Curriculum,

who feels that teachers should set parameters for content and allow

creativity to exist within the parameters for form. Although I haven’t

yet had a chance to test either approach, I feel that I would subscribe

to Peterson’s approach over Atwell’s, as I have seen the befuddlement of

students when given complete carte blanche to pursue any avenue they choose in their writing.At the end of her introduction, Atwell talks about how she morphed into a teacher who would practise the art of her own writing (by her own admission, a laboured process for her) on an overhead in front of her students. This practice struck me as a wonderful way to show the hard work of writing and demonstrate that teachers are also developing as writers while also teaching how to write at the same time.

Further,

both Atwell and Peterson write about offering students the goal of

publishing their work outside the classroom as an incentive for students

to produce polished writing. This isn’t an approach I have seen

teachers use recently. I remember this opportunity when I was in school

in the 1980s and wonder why it has fallen out of use. Could this be a

driving force for pushing students to become better writers?

Further,

both Atwell and Peterson write about offering students the goal of

publishing their work outside the classroom as an incentive for students

to produce polished writing. This isn’t an approach I have seen

teachers use recently. I remember this opportunity when I was in school

in the 1980s and wonder why it has fallen out of use. Could this be a

driving force for pushing students to become better writers?Overall, Atwell’s piece struck me as the story of the evolution of a teacher of writing who had to power through her own fears about how to teach, taking risks, and being a slow and challenged writer herself.

Monday, 12 January 2015

What is writing?

What is writing?

Is it simply putting pen to paper or fingers to a keyboard? Is it the

act of drawing symbols to represent sounds that form words? Is it more?

Or should it be less?

What is writing?

Is it simply putting pen to paper or fingers to a keyboard? Is it the

act of drawing symbols to represent sounds that form words? Is it more?

Or should it be less?In our first meeting for our course “Writing Across the Curriculum”, our professor asked us to do a short write to answer this question. Here is what I scrawled on my page: “Writing is putting thoughts and ideas to paper/screen using word craft to develop those ideas and thoughts.”

And now we are to write a short personal narrative about what we believe is important in writing in our content area.

My content area is History. Here is what I know about writing in History, at least at the academic level: it tends to be verbose, it tends to be dreadfully academic, it will, very often, turn people away who believe they love history. I love history but I don’t read history. I read stories and not stories written by historians. I stopped reading stories written by historians the day walked across the stage and took home my Masters Degree in History.

Historical writing should be storytelling with meaning. It should be pulling apart our stories in ways that we – laypeople, students, lovers of history – can find accessible. It should also be able to give us meaning in our stories and the stories of others without turning the lovers away. This is what is important in historical writing: telling a story and telling me why it matters in a way that I find inspirational, meaningful and engaging.

And that’s my story.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)